Mohlokomedi wa Tora

»On the 30 August 2018 at the Pretoria Art Museum I had the privilege of interviewing Lebohang Kganye on her solo exhibition Mohlokomedi wa Torai. The body of work that she has produced for this project gives two matriarchical perspective of her family narratives from where Ke Sa Le Teng her SASOL New Signatures winning video installation left of.

Mmutle Arthur Kgokong: Thank you Lebohang for agreeing to talk to me once more. Uhm, it is a very interesting exhibition from the winning work last year. When I first saw that it is an installation I was struck by the fact that you have included your old man in this exhibition to give us that familiar element in your work. I just wanna ask you, you know, how has it been for your to create a new body of work for this solo project? Having won the prize last year, how did you produce this work?

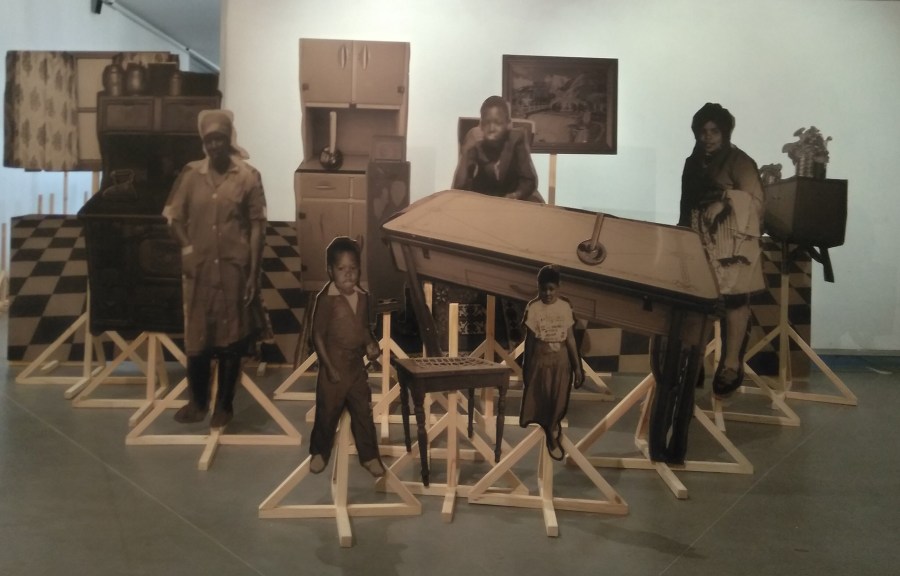

Lebohang Kganye: I think it is daunting, I think even when I won it, I have been thinking about working in a particular way or experimenting with something very particular which was installation. I have already done it but I have never really resolved it, I have been doing it for the animation pieces and for the photography element uhm people should experience the work in that was, but I have never resolved it how to… because it was temporal, because it was softer cardboard. How to make it stand. Or be more permanent if you can say so was not really resolved. So this was great because it allowed me the time I had a good budget to kinda figure out and experiment with that. So I think it was great because I already had an idea of what I wanted to do was an installation, even though I wanted it to move, and this and this and that, but it was just such a great starting point and I am extremely excited about how this part of it is resolved

MAK: For a while there, because you have used the word mechanics earlier on, and you say you wanted it to move, I could not help it but think, if you had a bigger space and a bigger budget as well and you had, for example the stands automated…

LK: I mean it’s very interesting that you use that term, I mean even I remember last year during the interviews I was like I wanna mechanize the cardboard cutouts, initially that’s been like the idea of where it should go uhm but there is also the realities about one needing technical expertise which is costly which I did involve initially for this to bring in someone to help me source materials, help me do this and that. So I think the process more than anything is good on a professional level to understand that there are times when you need to bring in certain technical expertise and say ‘I need you to resolve this is what I envision for this, you know those kind of things. But I think more than anything the direction that I want the work to go in is for it to move uhm, because there was

MAK: …you will need a production team…

LK: exactly, I will need a production team, you need a space because… I was away, I was away in Switzerland for three months on a residency and

MAK: that’s interesting

LK: and I imagined, even when I was writing the proposal for that residency I, more than anything I wanted to collaborate with people that work like in the more mechanical way and I was thinking about Switzerland and the history of watch making and all of that stuff and them understanding movement…

MAK: uhm-hu

LK: …and all that was like, it was so great to have been there to have been in a place where, to go to a flea market there are literally watches that are broken apart, there are like tools for making watches at a flea market! It’s like one person could selling two thousand pieces of watches …

MAK: it’s a tradition there

LK: its tradition

MAK: mechanization

LK: … exactly so it was so you know, but also it so amazing because it allows you to think about your work or the process of your artmaking in such a broader way it’s like, it frees you, I mean I never thought of my self as a traditional art maker, I’ve never – in as much as I have said that I come from a photography background – I have never regarded my self as a photographer

MAK: mhum – mhum

LK: so I think that this work speaks to that journey that conversation, so I think that my work more than anything is more than the conversation that I am having with my self

MAK: its biographical you would say

LK: yah exactly! For me that’s why I think that I appreciate the fact that the people get the work, relate to the work, but at the same time it’s quite personal and it’s like I own the process its like a diary (laughs)

MAK: we can bring our own readings but at the end of the day you know exactly…

LK: exactly I think that’s part that makes art making a bit difficult because it’s quite a vulnerable process; the making, having to give birth and giving the baby to someone you know uhm but you still try to own it but you almost have to share the baby with the world. so its quite a vulnerable process especially if you try, you try to move away from the medium that was recognized, that you got recognition from, you wanna try something else and you are hot sure if it will be received the same way; its always like a nerve wrecking process in that sense

MAK: and I uhm I see that you have continue to use the sort of sepia almost black and white tone in your photography uhm is this, you know, staying true to the archival material?

LK: definitely. I mean even if we think about uhm where the project started. I mean it started with me really collecting the photo album. So when I was visiting my family in the different parts and there is family members I haven’t met before and you kinda started a conversation and then at some point we would look at the photo albums or you ask to see the photo albums and then they show them to me. Sometimes I will re-photograph the photos and if it was not too far or if they were comfortable with it would scan the photos but a lot of it had either changed in colour because of aging or most of them were like quite…

MAK: brittle?

LK: … brittle yah, and I mean also the choice of material really speaks to that, it speaks to the idea trying to …that memory also being reliant on photographs also they become triggers for memory uhm but also how both photography and memory aren’t reliable sources and you cant say its factual because how I remember something its not how I remember it tomorrow it is two different things. So the choice of material really speaks to that non factualness or that temporal-ness of memory and of photographs

MAK: yes-yes uhm I find it very interesting that you have uhm juxtaposed for example the two farms here as well as the outside…

LK: yeh

MAK: …and the interior eh what was the initial approach to, for an example,

LK: mhum

MAK: …for choosing these settings? What was the idea because you could’ve chosen anyway f representing you know you could’ve went life size?

LK: yah

MAK: for example you know but this is almost at the eye, the easy eye level of the viewer you know

LK: okay, for me I think there were many many things. One, it wasn’t thinking about the space. This is basically where I grew up…

MAK: this is your home in Katlehong

LK: … this is my grandmother’s place in Katlehong. Most of my close family lives in Katlehong, so this is almost for me like the last scene you know and as my grandfather was the first one to move to the City and the rest of the family kind of came to Johannesburg though him, so he refused to work on the farms so he was like he is going to go to the city to try and find work which he eventually did and as apartheid was ending most of the family finally moved and uhm or when their farms got new owners and they were kicked of the farms and most of them kind of moved to the city through him. so this becomes like an end story uhm and this is my house in Katlehong and there

LK: my neighbors you know so all of these are like familiar settings especially these two, these speaks to my time as opposed to these two which don’t speak to my time because I didn’t grow up Ko Magaeng (in the rural area) uhm and all of them have…

MAK: so these are comfortable settings you know

LK: yah

MAK: … but these settings round of the narrative for you and the farm scenery is your origins even though you don’t have a direct connection to them

LK: mhum

MAK: these farms I find them interesting one respect…

LK: mhum

MAK: …this one shows affluence and the other one shows desolation. This is my last question;

LK: yah?

MAK: what was your thinking behind representing two perspectives of farming especially in a time in this country where the land question is such a heated debate? It is on the agenda, we don’t know how it is going to be resolved but it is there we have to deal with it. What was your thinking in bringing this, Eh because for me it is very relevant

LK: yah

MAK: But obviously you are the memory keeper here you know

LK: (laughs) I don’t know if I am a memory keeper…

MAK: laughs

LK: uhm I think your interpretation of it is very different from the stories or the intention behind these two scenes because I mean this scene being the first one…

MAK: this affluent farm

LK: (laughs) this affluent farm

MAK: (chuckles) with nice cows and everything and I can see the farmer, there is a church…

LK: yah

MAK: you can see there is sort of a religion you know nuanced in the work itself

LK: exactly! But it also speaks to so many things, it also speaks to the politics of religion you know uhm I think it speaks to so many things but I think the work touches on the things that should not be obvious I think people should want to spent time with the work, understand and try to interpret certain visual clues that have been put there

MAK: yes

LK: … so I am thinking about this is the story that I was told by my aunt who is now late and I feel like wow I did not get to spend… I met her when I went ko?, ne ele ko Orangefarm? No ko Qwaqwa so she is from Qwaqwa and I went there solely to try and do interviews with her because she moved with the family a lot. She got marred into the Khanye family so she is not from Batho ba Kganye but she really had a great memory, she got a great energy, she got married quite young…

MAK: she is the memory keeper?

LK: she is the memory keeper. She was amazing, I wish I had done many interviews with her uhm so this is the story that she got really excited about, about being married into Batho ba Khanye you know; she was like uhm when they paid fifteen cows as her lobola and she was like you know ga dikgomo tse ge ne di kena ko jarateng the way ne dile ngata ka teng ka be ka balega (you know when the cows were brought in into the yard they were so many I ran off)

MAK: [laughs]

LK: she was so excited that day!

MAK: almost like a stampede

LK: exactly! She was like she literally ran away, it is almost like that’s how, that story for her was so important for her thinking about; what I ask her about her about? uhm was something that stands out about being Motho wa Kganye you know and then she told me that story which I thought was so beautiful, but how, she literally shone up when she spoke about it and she kind of gave me visual clues about the place and what she remembered about being there because that was the initially farm and all that. So this scene is basically about that. But obviously in having other conversations with her you then visual choices that then speak to other things you kninda had a dialogue or conversations around uhm so that’s the story behind this scene.

MAK: yah and lastly this desolate farm?

LK: you know I think the entire body of work which is Mohlokomedi wa Tora which actually means lighthouse keeper right uhm for me what I found… I made a decision to use stories I was told by my grandmother and by my aunt who passed away. So its two stories that were told by my aunt and two stories that were told by my grandmother. But it is also the idea of who is the keeper of light, this idea of… because our surname means light. But because I centered the project around my grandfather initially the research was around my grandfather as the first person to move to the city you know

MAK: yes

LK: … but I actually realized that a lot of the stories and the research that I have been gathering was actually from women, my family is predominately women. I then decided I need to relook…

MAK: reconfigure

LK: …reconfigure it. I was raised in a house where there was just women. I think my grandparents have six daughters and one son. So it was also me actually rethink about this. So this scene was another story from my aunt where she was saying that there were these boys who used to be milkmen or who deliver milk uhm and they had like this truck and they will come, and they’d always like scare the horses when pulled very close to the horses and one day this horse tried to run away and she kind of got hooked in the process and it kinda of dragged her and somehow they got her off it. But like how she narrates the story for me it’s like so beautiful because it’s so visual you almost feel like you are in that time uhm so these are the stories around the scenes.

MAK: Thank you

LK: (Laughs)

Mmutle Arthur Kgokong: Thanks for a wonderful exhibition, thank you

Lebohang Kganye: thank you

*Mohlokomedi wa Tora is on at the Pretoria Art Museum until 7 October 2018.

Spring

© Mmutle Arthur Kgokong 2018

follow at twitter @mmutleak